A Creature of New York

A Reviewer-at-Large Goes 15 Rounds with New York City and the World

Ever go to see a band, and the drums start motoring, the guitars crank up, the bass begins to thud, you feel your head starting to move up and down, and you're caught up in the feeling that you're about to be rocked… but then, as the song goes on, you find yourself waiting, and then you're still waiting, and the hook doesn't come… and they play another song, and then another, each one louder and more raucous than the last, and you realize that, although the band has all the raw energy it needs and more, and solid musicianship too, somehow… the songs just don't go anywhere? And yet the band keeps on playing, fruitlessly.

It can happen in theater too, and such is the case with Lavaman, Casey Wimpee's literally visceral new play, currently running through July 18 at the Ohio Theatre as part of Soho Think Tank's Ice Factory 2009 summer festival. The title character is an animated monster created by Arnie (Michael Mason) for his comic book—or, as he insists, "graphic novel."  The live action is interspersed with a number of amusing Lavaman animations, but the one it opens with is the most telling: Lavaman's cartoon bout of painful, multicolored flatulence and diarrhea turns out to presage the play's logorrhea.

The live action is interspersed with a number of amusing Lavaman animations, but the one it opens with is the most telling: Lavaman's cartoon bout of painful, multicolored flatulence and diarrhea turns out to presage the play's logorrhea.

First it's Gill (Cole Wimpee), an alcoholic-turned-vegetarian with carpal tunnel syndrome and an aching back, who can't stop ranting and shouting about the punk rock band he used to have with Arnie's dead twin brother. (That's right, a dead twin brother. Everyone here has dead parent or sibling issues.) Gill, it seems at first, is supposed to be one of those Lanford Wilson-style flame-on characters who torches other people out of their complacency. But his voluble energy doesn't drive the plot or change anyone's life; there's mostly void around him–lots of sound and fury, not signifying much. The script has to rely too heavily on musical references and other pop-culture signifiers to score characterization points on stage or laughs from the audience.

Enter Dino (Adam Belvo), the third member of this sad triumvirate, a former bandmate who has "sold out" and gotten rich by day-trading (it's 1999). Dino is a larger-than-life personality, even more so than Gill. Dino’s own issues–his have both parental and sibling elements–have propelled him on a globe-trotting carnivorous rampage. Now he's back, hoping to celebrate his birthday with his old buddies in gruesome style. But Dino, like Lavaman, is a cartoon character; his preening and howling drive away any empathy we might have started to feel for stuck-in-the-past Gill or creatively blocked Arnie.

Told in a series of flashbacks, the story zeroes in on the events leading up to Dino's protracted, violent end. But unlike the punk rock songs the characters listen to and talk about, the play lacks a hook, for all its vehement verbosity and claustrophobic fury. In trying so hard to be provocative, this much too long play ends up provoking only exhaustion and a mild nausea.

Lavaman closes July 18. Soho Think Tank's Ice Factory 2009 continues through Aug. 15 at the Ohio Theatre, 66 Wooster St., NYC. For tickets please visit Smarttix or call 212-868-4444.

Photo by Kalli Newman.

Twisted is a modest, uneven, but often diverting collection of short one-acts. It opens with the most substantial and ambitious of the evening's five plays. In Matt Hanf's Teddy Knows Too Much, the hefty actor Peter Aguero deadpans the role of three-year-old Billy, whose toys—a plush bear, a Dick Cheney mask, a rubber duckie—are his only confidantes.

While these imaginative figures can be alternately understanding or sinister, the adults around Billy are universally insensitive. ("I think I'll wear the emerald earrings you got me for our last fight," wisecracks his mother, while his father considers leering at the violence in The Sopranos to constitute a valid "family night.") Billy fights back the only way he can: with ever-intensifying mischief.

The parents are written and played as such churlish, career-obsessed caricatures that the play tends to overstate its case; a small boy's imaginative world can be terrifying even in the kindliest of families.  But Aguero's brash, funny performance and the lines Hanf gives him elevate the show above easy satire. "Being good is what is expected," philosophized the overgrown, biker-bearded toddler, "and what is expected is rarely rewarded."

But Aguero's brash, funny performance and the lines Hanf gives him elevate the show above easy satire. "Being good is what is expected," philosophized the overgrown, biker-bearded toddler, "and what is expected is rarely rewarded."

Mark Harvey Levine's "The Kiss" is a slight but well-scripted scenario of two friends (Flor Bromley and Jonathan Reed Wexler, both very good) touching on feelings that haven't been touched on before. It's followed by two skits that dramatize comically bizarre what-if situations, in the style of Saturday Night Live skits. They're one-joke pieces, so I won't give away the jokes, but unlike some of the abovementioned TV skits, they're pretty funny—especially Justin Warner's "Head Games"—and they don't overstay their welcome;  suffice it to say there's a garden shears, many pastries, and a very funny Lindsay Beecher as a teenage Salome.

suffice it to say there's a garden shears, many pastries, and a very funny Lindsay Beecher as a teenage Salome.

Ms. Beecher returns as a coke-addicted exotic dancer for the evening's final play and its only real dud. In "Party Girl," a young man (Billy Fenderson) attending his cousin's bachelor party discovers that one of the strippers hired for the party (Becky Sterling) is… his girlfriend. Despite the pointed efforts of the talented cast, the play reads like a bloated drama-class exercise—its potentially interesting recipe turns out to be a pot of poorly cooked gruel. It's a downer of an end to an otherwise upbeat and amusing evening.

Twisted is the Rising Sun Performance Company's third annual one-act series. It plays at at UNDER St. Marks through July 26. Tickets at Smarttix or 212-868-4444, or at horseTRADE. Photos by David Anthony.

No one does bedroom farce like the British, and a fine example just blustered onto the New York stage with the Vital Theatre Company’s sharp new production of Robin Hawdon’s Perfect Wedding.

A man wakes up on his wedding morning in the hotel’s bridal suite with a naked woman he doesn’t know. Hilarity ensues, and a touching love story too. Teresa K. Pond’s sure-handed direction shapes Hawdon’s snappy dialogue, slapstick humor, and blurry maze of plot twists into a cheery evening of laughs and good feeling.

The dialogue has been slightly Americanized, but the British pedigree shows, not only in the door-slamming, under-skirt-hiding story, but in the occasional unnatural phrase  (e.g. “very well”). However, 99 percent of the time, the actors (and the adaptation) hit just the right notes of absurdity, desperation, and overdoing it.

(e.g. “very well”). However, 99 percent of the time, the actors (and the adaptation) hit just the right notes of absurdity, desperation, and overdoing it.

Elastic-faced Matt Johnson plays Bill, the panicked groom, with a sweetly expressive mixture of bug-eyed fear and little-boy-lostness. The beautiful Amber Bela Muse does a nice job with the straight role of the clueless bride, although there’s a late scene or two where she seems a little too calm for a bride on her wedding day.

The effervescent Dayna Graber threatens to steal the show as the wisecracking, mint-popping hotel housekeeper who gets caught up in the proceedings. But Tom (Fabio Pires in a very promising Off-Broadway debut) distracts us with his finely tuned fury upon discovering that Bill’s best man is by no means the only role he’s destined to play in this careening plot.  And Kristi McCarson, in the initially thankless “other woman” role of Judy, captivates with her stark revelations in Act II.

And Kristi McCarson, in the initially thankless “other woman” role of Judy, captivates with her stark revelations in Act II.

Ms. McCarson also looks stunning in the wedding dress, which gets its own credit, being on loan from English couturier Jane Wilson-Marquis. If you like this wedding dress, you can go to site >> here which sells similar designs! It’s quite a gorgeous garment. I won’t give away how Judy ends up wearing it. Suffice it to say the bride’s mother (Ghana Leigh) is involved.

Enough. Whatever troubles you may bring with you into the theater, this crackerjack production will make you forget them, at least for a rollicking hour and forty-five minutes. Perfect Wedding plays at the Theatres at 45 Bleecker Street, New York, through Aug. 2. Get tickets online or call (212) 579-0528.

Photos: Sun Productions, Inc.

Craig Jackson, Damn the Roses

Music is a funny, time-twisting business. With five albums to his name, Craig Jackson just got nominated for "Best New Band" in Nashville's Toast of Music City Awards.

Though Jackson's sound is commonly described as "Americana," at times it can suggest Tom Petty and Don Henley and 1970s-80s heartland rock as much as it does the polished but back-to-basics sound of Lucinda Williams and Jim Lauderdale. Too, Jackson's youthful, slightly scratchy voice is more typical of pop and alt-rock than of traditional country and Americana. Still, beginning with the second track, "Everytime You Leave," he slides into modern (but not "commercial") country music territory.

These terms, of course, are labels, and as such fairly unimportant. His voice, whatever "type" you call it, gives his arrangements a warm glow and a melded softness that carries through pretty much the whole disc. In general, these songs take their time, maintaining laid-back but emotionally potent moods. Highlights include the war story "1941," the keening title track, and the catchy pop of "Simple."

The Iveys, The Iveys

These Iveys are a band of three young siblings out of West Texas, not the now-obscure 1960s Iveys that evolved into Badfinger. But there is something pleasingly retro in their focus on thoughtful pop songwriting and glittering vocal harmonies.

The catchy soft-rock nuggets "Leave It To Love" and "Going the Right Way" are the best tracks on this eight-song disc; the single, "Back When It Was Our World," is solid too, though, to my ear, not quite as inspired. The slower tunes, like "The Promise," "Whispered Words," and the meandering "Your Love Now," though bedded in fragrant arrangements and decorated with sweet, nicely understated harmonies, don't have the pop flair of the more upbeat tracks. I suspect that as the Iveys' lyric-writing matures the emotional impact of their music will become more consistent.

Despite my reservations, this is a promising debut from a group that could, as likely as anyone, emerge as a Fleetwood Mac for the new century – without the messy divorces.

Bobby Long, Dirty Pond Songs

Staying on the youth tip, here comes Bobby Long. I almost didn't listen to this CD. The black-and-white sensitive-boy cover shot, the Myspace provenance, and above all, the fact that Long, still a London college student, had become known only because Robert Pattinson sang a mush-mouthed version of a song Long co-wrote in the movie Twilight – all these factors suggested that this was overhyped fluff.

Hyped, yes. Fluff, not so much. With raw vocal power and smart, evocative lyrics, Long is a folksinger with a spirited intensity that puts him outside and above the masses of singer-songwriters roaming our cities, towns, and social networks.

His original voice comes through in a combination of factors. One is his solid guitar playing, which takes a lot from the hard-strummed sound of the early folk-pop crafters like Bob Dylan and Dave Cousins. A more unusual factor is that, unlike most modern songwriters, Long seems to really like language, layering and intertwining his thoughts and images. Meanwhile, echoes of Nick Cave and David Bowie and Leonard Cohen shoot through his melodies, though many of the songs are rooted in real traditional folk idioms (think the Child Ballads).

Long's debt to traditional and Dylan-esque folk is evident in "Who Have You Been Loving," where detailed imagery in the verses alternates with a repeated one-line chorus – but with the composition juiced up by delaying that chorus. "The Bounty of Mary Jane" resembles an old, sad ballad: "I will fall upon this town / To call your name, my sweet suffragette / my sweet Mary Jane." Songs like the waltzing "Being a Mockingbird" would fit right into an Americana playlist today, but Long's undisguised working-class British accent reminds us, as Billy Bragg did, how the American Appalachian music tradition is deeply rooted in ballads from the British Isles.

Some parts of some songs don't always seem to quite make sense together, but, because Long sings with such an honest tone, the discontinuities mostly serve to hold the listener's interest. The melody of "Penance Fire Blues" at first echoes Bowie's "Jean Genie" and the song (coincidentally?) contains yet another curious mention of "suffragettes." Then it resolves into a cry to "let me run" and a worry about finding one's feet.

Though the songs don't always hang together, and a few are forgettable, this is a perceptive and rich collection. "I'm afraid to die," Long writes in "Left to Lie," the most powerful track on the disc: "I'm nearly old / I'm almost young / So I'm told." Shades of Dylan's My Back Pages, yes, but clinging to and building on those hoary roots in his own way. The CD will be released shortly via Long’s Myspace page, where several singles are already available including “The Bounty of Mary Jane.”

Five humans, all with troubles, assemble at a Dunkin' Donuts wearing Halloween costumes. After raising money for their group home for the disabled, the three residents and two staffers coalesce into a bickering but affectionate group. On some level, as playwright Kristin Newbom demonstrates, the disabled and the staffers aren't so different. But that's about as much of a moral as can be extracted from the three scenes that comprise this compact one-act; Newbom's witty script is about as un-preachy as a play can get.

In large measure, the play is about money. First, it's physically present — the tables are covered with the dollar bills our heroes have raised and are counting. In fact, counting the money is the silent breathing action behind the play's dialogue.  Second, money is constantly presenting itself in the abstract, as the characters worry about the group home's funding, their own financial situations, and whether they can take a dollar from the pile to buy a cup of coffee.

Second, money is constantly presenting itself in the abstract, as the characters worry about the group home's funding, their own financial situations, and whether they can take a dollar from the pile to buy a cup of coffee.

It's all very funny — bordering on the absurd, yet believable and touching. Jerry (Andrew Weems), who walks with crutches, is a philosophizing motormouth whose rampant fabricating hides a well of loneliness. Wheelchair-bound Shelly (Birgit Huppuch) gets a lot of the biggest laughs with a stream of innocent non sequiturs; revealing some of the circumstances of her life in quick, unexpected darts, she's the exposed heart of this makeshift family. Gary (Debargo Sanyal), who has a severe neuromuscular dystrophy and uses a motorized wheelchair, hardly says anything out loud, but we do learn, in a quite startling way, what has been occupying the mind inside his uncooperative body.

The staffers are in sadder states than their charges. Scott (Greg Keller), outwardly a handsome young man, suffers from crippling anxiety that leaves him hyperventilating and feeling like a "barren landscape" with a fire in his belly. Lonely Ann (Christina Kirk), a single mother, fights off creditors while nursing an unrequited crush on Scott.

The cast shines, Ken Rus Schmol directs smoothly, and Kirche Leigh Zeile's costumes are hilarious. But the real star of this show is the sparkling script. Ms. Newbom has a surefire sense of rhythm. Watching this play is like listening to a brilliant piece of music executed with precision and filled with surprises.

Telethon, the third and final play of Clubbed Thumb's Summerworks 2009, closes June 27.

Photo by Carl Skutsch. (L-R): Andrew Weems (Jerry), Birgit Huppuch (Shelly), and Greg Keller (Scott)

Dotting the fields by the road around the Caribbean island of St. Kitts are hundreds of white birds. Marveling at the beauty of these graceful, long-necked animals, we asked Solomon, our hotel's driver, what they were.

"Egrets," he replied. "They look pretty, but they're damn nuisances. They shit all over my pool."

It's all relative. Here in New York we've got open-air double-decker tourist buses all over the place. When I'm walking, I like to see the buses. It's fun to watch the tourists gawking at the skyscrapers and famous sights that to me are just part of the everyday scenery. It's useful, and enjoyable, to be made aware of different points of view.

When I'm trying to drive downtown, though, the buses are a nuisance, clogging up the intersections like mis-oriented vitamin pills in your throat. So: another point-of-view shift, this time all within one person, pedestrian vs. driver. Every conceivable point in space or time is (theoretically) somebody's point of view, and all those points of view are out there criss-crossing and opposing, separating us from one another and dividing us internally too.

Somewhere, terrain-wise, between a small, underdeveloped Caribbean island and the heart of Manhattan is the suburb I grew up in. It was a good place to be a kid. A few years later, it was a boring place to be a teenager. It hadn't changed; I had. Now I've shifted yet again, looking down my nose at suburbs altogether.

Yet even though I haven't lived in one in decades, when I visit suburbs in other areas I feel superior and defensive about my own home town: we had sidewalks, why don't you have sidewalks? What if someone wants to go for a walk? Who planned this town? Meanwhile someone from that sidewalkless community is probably driving through my old town thinking: how can people live in a place that doesn't have any hills?

It's amazing, when you think about it, that we function and get along as well as we do. Sure, there are always wars going on, and people stereotyping, despising, and oppressing other people, countries, races… suburbs. But countries survive for centuries. And we have not blown up the planet, nor wiped ourselves back to the Bronze Age, despite well over half a century of capability.

We may have point-of-view problems, but we did evolve as social animals. That gave us the smarts we constantly use to both help and hurt ourselves individually and collectively. The fact that people can live in small groups or large ones, in every kind of terrain, and within a wide variety of social institutions, tells us something important:

There's hope for humanity. There's hope for the Earth. There's even hope for some of the beautiful creatures we share the planet with.

Just as long as they don't shit in my pool.*

—

*Metaphorical. I don’t have a pool.

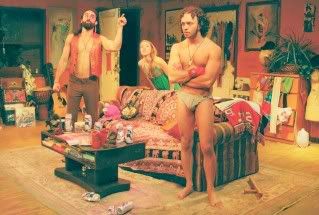

A chaotic apartment: dented beer cans, assorted musical instruments, dirty walls, kitschy objects strewn about. Another play about angsty twenty-somethings trying to decide what to do with their lives? Look again: the revolutionary banners and scrawled slogans add up to more than the stuff of typical college-age rebelliousness. So: a play about 1960s radicals? Look (and listen) yet again: it's 2009, iPods are everywhere, Barack Obama is President, and this is a play by the Amoralists. Hackneyed convention is not on the menu.

At the center of the tale is a reverse-Prodigal Son story. Billy (James Kautz), a drug-addicted revolutionary and the emotional focal point of an anarchic sexual foursome, receives a visit from his straight-arrow younger brother Evan (Nick Lawson). Though Billy is the one who is estranged from his family, Evan's manic, hilarious frat-boy wiggerspeak is as bizarre and incomprehensible to Billy's tribe as the group's four-way "marriage" and off-the-economic-grid lifestyle are to him and the outside world.  But Evan quickly forms an attachment to Dawn (Mandy Nicole Moore), the newest, youngest, and most honest member of the foursome. And when bad news arrives in Act Three, wrenching complications ensue.

But Evan quickly forms an attachment to Dawn (Mandy Nicole Moore), the newest, youngest, and most honest member of the foursome. And when bad news arrives in Act Three, wrenching complications ensue.

Playwright Derek Ahonen has a finely tuned ear for the way his Communist-Anarchist-Environmentalist heroes and heroines talk. The play skewers their free-love and pop-psychology platitudes, while loving the characters to death at the same time. I say "the play" because while Mr. Ahonen may be responsible for the dialogue, the Amoralists truly are, as their mission statement proclaims, an "actor driven" company. It feels as if these actors were born to play these parts. The play is a perfect whole — not for a second is the theatrical spell broken. And somehow the political and moral message survives all the mockery.

Matt Pilieci, who plays the volcanic, hyper-vital yet death-obsessed Wyatt, and Mr. Kautz are reprising their roles from the 2007 production. The impish Ms. Moore isn't, but she is just as perfectly locked into her role, and the same is true of the darkly focused Sarah Lemp, who plays Dear, the fourth member and the group's mother figure. Each of the four can dominate the stage in one way or another; together they're an ensemble of scary intensity, one minute boiling in anger, the next erupting in crazed funnyness, yet always, in their overcooked way, seeming to truly love one another.

As always in these apparently Utopian situations, there turns out to be a sugar daddy. Donavan (Malcolm Madera), the rich owner of the building, uses the money-losing restaurant Dear and Wyatt run downstairs as a tax write-off, paying them and their lovers in room and board. Since this is a New York City story, it isn't giving too much away to mention that the realities of real estate play a part in the plot. But the meat of the play is its acidic depiction of the fearsome foursome through the juggernaut of Act One, and the challenge posed to them by Evan's cynicism in the slower and slightly too preachy Act Two. When things begin to fall apart in Act Three, it feels inevitable; these characters are simply too big for the temporarily comfortable life they've created for themselves.

And the center, the emotionally volatile Billy, cannot hold. Running his radical newspaper, engaging in frantic phone conversations with his revolutionary compatriots in Mexico, defusing conflicts right and left, he is a fount of endless nervous energy, but at the same time he's frozen in place, an idealistic man out of time, powerless to effect real change in the world. When this paralysis manifests physically, Billy is reduced to a raw lump of feeling, like the horribly transformed fly-creature tumbling out of the transporter pod at the end of David Cronenberg's The Fly. It's a captivating moment, and it sends us reeling into the street feeling provoked, enlivened, even a little bit enlightened.

Pictured: Matthew Pilieci as Wyatt, Mandy Nicole Moore as Dawn and James Kautz as Billy. Photo by Larry Cobra.

The Pied Pipers of the Lower East Side by The Amoralists runs through June 28 at P.S. 122. Visit the P.S. 122 website for times and tickets or call 212-352-3101.

Trevor Alguire’s music is rooted in the traditions and commonplaces of country music, but it has a modern sensibility.

Trevor Alguire, Thirty Year Run

This world always has room for new easygoing, rootsy country music, as long as the songs are good, and Ottawa-based Trevor Alguire's new disc frequently hits the target. "Full of Rust," a basic, fiddle-charged, two-and-a-half-minute gem, opens the disc strongly. Other highlights include the slow-drawl waltz of "Troubles Me So" with its creamy harmonies, the insistently elemental "Like Old Times," the hard-edged, quirky "The One," and the rollicking "These Words," which asks an unusually honest question: "Would you hold me to / These words I say to you?"

The mostly brief songs don't overstay their welcome, making their statements and closing up neatly. "Away From You Now" is an exception, taking a while to get going but bearing fruit if you're in a relaxed, stick-with-it kind of mood — and that's the mood this disc will put you in, notwithstanding its sprinkling of up-tempo tunes.

Alguire sings in a smooth, unprepossessing, slightly vulnerable baritone that's both expressive and soothing. On the instrumental side, the performances are impeccable. Fine mandolin work by Gilles Leclerc and assured fiddling by Michael Ball stand out.

Melodic conventions pull certain songs down into country cliché, but most of the time Alguire stays on the honest side of the fine line between accessible and unoriginal. The sweet title track helps prove that although his music is rooted in tradition and country music commonplaces, he has a modern sensibility. It tells of a man who's spent his whole career working in a paper mill, but now those days are gone: "There's no such thing as a thirty year run today / Son, you're fired."

Stillhouse Hollow, Dakota

If Trevor Alguire is rootsy, Tennessee band Stillhouse Hollow is downright lo-fi. Their signature sound has a ragged charm, acoustic and old-timey, with banjo, mandolin, harmonica, and upright bass more prominent than guitar. The clear, light-spirited vocals from primary songwriter Nathan Griffin and the boys have a youthful simplicity with just enough quaver to convince. Standouts: "Strollin' In," which suggests the Byrds' country period; the jaunty "Painfully True"; and the silly, sad-eyed "Pimp Hand."

Hot Monkey Love, Speakin' Evil

Hot Monkey Love hits home with a barrage of Chicago blues all twisted up with strands of Southern rock and soul and a gritty New York City attitude. The disc opens with a crushing rendition of "Palace of the King," written by Leon Russell, Don Nix, and "Duck Dunn" in honor of the great Freddie King. (John Mayall also covered the song on a recent album.) The band is equally at home with Jimi Hendrix's "Angel," and lands a surprisingly tasty cover of Alicia Keys's breakout hit, "Fallin'."

The band can succeed with a song like that, first because they're good arrangers, but also because of clear-voiced singer Jack O'Neill's ability (like Lou Gramm, whom he resembles vocally) to convey a sensitive lyric as easily as he can belt out a rocker. This serves him very well in one of the strongest original songs on the disc, "Weight Off My Shoulders," a gorgeous duet with guest Antonique Smith (of Rent fame). Another great arrangement makes the original "Stay" a highlight, and the funky blues of the title track (also an original) brings Son Seals to mind. Overall the band's own songs stand up well against covers by the likes of B. B. King, Robert Johnson, and Artie White, and that's saying a lot.

Fans of electric blues can't go wrong with this disc. It has a little of everything, but a muscular, authentic blues sensibility infuses it all.

The oddly titled “Ore, or Or” is an artfully constructed, well-aimed, and resonant story of a modern New York City love triangle.

I have now seen all three productions in the inaugural series from the new tripartite Theatre of the Small-Eyed Bear, comprised of three Off-Off Broadway companies which have economized by sharing production costs, space, and design teams, subsuming their individual identities as well.

From a technical standpoint, the operation has been a success. All three plays, for example, share one easily modifiable set (by the talented Elisha Schaefer). There's one publicist, one graphic designer, one technical team. All good.

As for the productions themselves, they're a mixed bag. David McGee's Mare Cognitum, reviewed last week, had some fine writing and very good performances, but sacrificed dramatic integrity for philosophical meandering.

Lenny Schwartz's Squiggy and the Goldfish is painted in brighter, childish colors, which lends weight to its theme of abuse, but it too suffers from a weakness of focus.

At the center of Squiggy is a brave, sharp performance by Josh Breslow as the title character. Abuse at the hands of his suicidal father has made him a cutter of long standing, though he's successfully hidden his scars from his ineffective, half-unmoored mother (Dana Aber). Terrorized by his cruel fiancée Veronica (the excellent Katrina Ylimaki) and her violent father (Jonathan Miles), Squiggy gets no relief even in his dreams, where a horror-movie psychiatrist and a nightstick-happy cop chase him through paranoid fantasies.

Salvation appears in the form of Blossom (Elyse Ault), a clerk at the pet shop where Squiggy goes to seek a cure for his excessively voluble goldfish, Goldie. This animal spirit, played with comic bluster by Eric C. Bailey, leads Squiggy through the this-is-your-life sequence that forms most of the action, and at first Goldie is a very funny beast. But Mr. Schwartz and the director, Michael Roderick, relegate him further and further into the background as they gradually reveal the story of Squiggy's unfortunate life. In the process we learn more about the women he loves as well – his mother, his fiancee, and then Blossom.

As they reveal themselves, the characters stimulate aches of recognition, but the effect is too often subverted by Recovery Movement catchphrases, characters stating the obvious to one another, and narrative inconsistencies. Goldie informs Squiggy he is to die in a week, but a revelation at the end seems to tell a different story. Mr. Breslow does absolutely all he can to keep the play centered, but he can do only so much.

Duncan Pflaster's Ore, or Or, the most successful of the three plays, also makes use of dream sequences, but here they are in the context of a well-rounded, coherent drama about relationships and racial identity. It is also staged with much starker realism than the other plays; though it's the same theater, we feel we're in an entirely new and somehow larger physical space. The crafty lighting and brittle, economical set create the illusion of more depth on stage, and Mr. Pflaster lights it up with an artfully constructed, well-aimed, and resonant story.

The action flows quickly, thanks to director Laura Moss, and that's good, because these characters have much to go through. The tale is essentially a classic love triangle, with the beefy Calvin Kanayama (E. Calvin Ahn) at the apex. He seems to love his new girlfriend, down-to-earth Debbie (Elizabeth Erwin), but lusts after the lithe and forward Tara (Clara Barton Green). Along the way he bonds with Sean (Shawn McLaughlin), Debbie's gay roommate, who, through no fault of his own, suffers from knowing more than he wants to about his friends' love lives. In creating a supportive and single "gay best friend," Mr. Pflaster flirts with cultural stereotype, but comes out pure, as Sean flowers into the most likable and vivid character of all.

The action skips deftly through one seriocomic situation after another. The mostly solid cast has fun with video games, food poisoning, Star Trek, and Sean's adventures as a substitute teacher. Periodically, a gong and some evocative shakuhachi music divert us into one of Calvin's dreams. These have been touched off by his work at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, where he's researching some gold figures that just might come from the legendary Yamashita's treasure. This sub-theme is an appealing, ornate framing device, though perhaps not totally necessary, as the imperfect, realistically rough-edged New Yorkers living their laughing, heartbreaking lives in front of us are intriguing enough by their plain selves. Still, without the dream sequences, we wouldn't have the lovely costumes and the great score, and they do provide some neatly dramatic moments as well, so who's complaining? The car may be a little used, but the paint job is smooth and the engine runs very well. Climb aboard; this is a worthwhile trip.

Squiggy and the Goldfish and Ore, or Or play in repertory through May 30 at the Workshop Theater, 312 W. 36 St., NYC. Tickets are only $12.

This extravagant, sexually charged dance-theater piece is a visionary re-imagining of the story of Adam, Eve, and Lilith.

Austin McCormick's Company XIV is back with another extravagant, sexually charged dance-theater piece of the kind only they can produce. Where last year's Judgment of Paris drew on the young choreographer's study of French baroque dance (pre-classical ballet), the dancing in Le Serpent Rouge is more modern; but again the company creates a visionary re-imagining of a classic story, this time the legend of Adam, Eve, and Lilith.

In this telling, Adam (John Beasant III) is first paired with Lilith (Yeva Glover), but although the sex is great, he rejects her because she has "no soul" and what he needs is a soulmate. Nevertheless Adam continues to desire Lilith, both before and after the Fall, and this provides the production's ongoing tension as the wonderful cast of five dances through elegant and sensual enactments of the Seven Deadly Sins.

Narrating is Gioia Marchese as a Ringmistress in an outfit worthy of Baz Luhrmann's Moulin Rouge, also functioning as the Devil, constantly proffering the infamous apple of the Tree of Knowledge to Eve (Laura Careless).  Appropriately, the set is a circle, both cagelike and circusy. Coiling through is the serpent, evoked by Davon Rainey, who also delivers several interesting and illuminating (and highly crowd-pleasing) drag numbers.

Appropriately, the set is a circle, both cagelike and circusy. Coiling through is the serpent, evoked by Davon Rainey, who also delivers several interesting and illuminating (and highly crowd-pleasing) drag numbers.

But none of this factual description conveys the lurid opulence of the production. Swings, a giant chandelier hung low to the ground, a focused rain of water, a huge mirror (for Eve to lose herself in), light bondage, near-nudity, and the world's first threesome are only a few pieces of the puzzle. The choreography is continually expressive and beautifully realized by the amazing dancers; the movement is descriptive, never abstract, occasionally a little repetitious, but the spell holds for the production's full 70 minutes.

The score plays a big part in establishing and maintaining the mood. As with Judgment of Paris, it's sewn together from a variety of sources, this time from the likes of Eartha Kitt and Peggy Lee, Cecilia Bartoli and Nina Simone. The text includes a Bukowski poem and passages inspired by Thomas Mann along with elements from the Bible and the Apocrypha. While dance predominates, the cast prove themselves capable actors. Ms. Glover is both regal and slinky, Ms. Careless a package of joy and pain and anger successively, Mr. Beasant a compact, darkly human Everyman. Ms. Marchese and Mr. Rainey are pure over-the-top delight, as they were in Judgment of Paris.

Given the dark material, there's surprisingly little menace in the tale. One gets the sense that Mr. McCormick and his troupe take such pleasure in their work that real evil, even in circus guise, can find no purchase on their stage. But no matter; this is a richly woven, thoroughly rewarding entertainment, well worth the excursion to the company's beautifully converted tow-truck pound near the Gowanus Canal. Get tickets before it closes on June 6!

Photo by Steven Schreiber. (L-R): Davon Rainey and Yeva Glover

Songs by Journey, Whitesnake, and even Amy Winehouse are becoming show tunes.

After seeing this week's premiere of FOX's new high school musical comedy-drama, Glee, and recently catching Rock of Ages on Broadway, it struck me how classic rock, pop, and pop-metal songs from the '70s and '80s have turned into show tunes.

There used to be a clear distinction between "show tunes" and other songs. Show tunes, as their name implies, came from classic Broadway shows, and sometimes from films of Hollywood's golden era. Popular music that you heard on mainstream radio — whether pop, rock, or country — lived in a separate cultural world. Not that you couldn't like both. But you didn't hear them in the same context.

Now Journey's "Don't Stop Believing" is a show tune. Who would have thought?

I blame Mamma Mia, which helped spawn Jersey Boys and other semi-revues based on popular music. The end is not in sight; there's even a show in development based on Green Day's American Idiot.

Journey's hit, along with many other hard-rock anthems and ballads of its era, form the score of Rock of Ages, the new Broadway hit musical. "Don't Stop Believing" also famously accompanied the controverial final scene of the last episode of The Sopranos, and now it fuels the grand production number that climaxes the debut of Glee, a new show about high school glee club performers.

It's not a current song, by any means, and not the kind of music we'd expect today's high schoolers to be into. But the theater kids are into it, at least on Glee, and why? Because just like a classic show tune, "Don't Stop Believing" is a fundamentally good song that's also deliciously over the top. The kids also make a very funny production number out of Amy Winehouse's "Rehab," a much newer song that shares those traits.

Of course there's always been "showiness" in pop and rock. For every sinewy, straight-up act like Bruce Springsteen and the Rolling Stones, there's an equally successful act that's more self-consciously showy: the glam-rock of Bowie and T-Rex, the grandiloquent Freddie Mercury of Queen, the theatricality of Pete Townshend's Tommy and Quadraphenia scores, the stagy productions of early prog-rockers like Genesis, and of course the arena-pop music extravaganzas of the likes of Cher, Tina Turner, and Madonna.

But there was still a separation. And when rock did start to appear on Broadway, it came in the form of new shows with new music written for them (Hair, Godspell), or material that already existed in "show" form, like Tommy, which was conceived as a rock opera from the start.

Once Abba came to Broadway, there was, it seems, no turning back; it was just a matter of time till Rock of Ages appeared. And just as theater geeks of the '70s took inspiration from the music of an earlier era — what we knew then as "show tunes" — the kids of a new TV show circa 2009 (not to mention American Idol and its cohorts) go back to what is, for them, a correspondingly early era, the '70s.

So pop music feeding the theater is a well-established thing by now, but it's still a bit of a shock, if a happy one, to see Journey, Whitesnake, and Amy Winehouse becoming show tune fodder. Back in the '80s, "oldies" radio stations played doo-wop. Now they play music from the '70s and '80s. The definition has changed. And the same has happened to the meaning of "show tunes." Musical eras are like waves on the beach, arriving one after another, each one crashing, then falling back into the sea to feed the next wave. Cowabunga, dude! And don't stop believing.

Like a chunk of green cheese with an emerald inside, this meditation on the power of imagination contains a hard, bright nugget.

Mare Cognitum follows three twenty-somethings reliving the wide-eyed excitement of intellectual discovery they experienced in college. Or rather, that's what the playwright himself, David McGee, seems to be indulging in.

There's promise in his effective opening scene, and dramatic flair in several other segments along the way. At the start, Lena (Devon Caraway) and Jeff (Kyle Thomas) can't see eye to eye about whether they should bother joining the anti-war protest marching past their apartment building. Jeff decries the crowd's lack of focus; Lena, too, casts a critical eye, but feels an urge to join her own passion to the masses'. Their compromise involves protesting at home without merging with the mob; "Nobody's listening to them either," sighs the withdrawn, Hamlet-like Kyle, "and at least we'll be warm."

When the friends act out the job interview, it's the first instance of a role-playing trick that works better during a few later scenes, when it's used more crisply to turn the living room into a classroom and (too much later) a rocket ship. The interview itself turns out to have been something else entirely; Thomas has been keeping a secret from his friends, a secret which leads to more college-coffeehouse discussion but little character development. Though poor vexed Thomas seems at first to be going against character to seek some kind of enlightenment, when the chance comes for him to really engage his imagination he retreats. He's a tragic character in this sense, yet at the end he's right back where he started — just a guy looking for a job, not sure yet what he wants to do with his life.

The play's problem is that not enough happens. The characters' exchange of ideas can't carry 90 minutes of drama. When something does occur — notably, Lena's spiritual awakening, and at the end, a half-real trip to the Moon — the production springs to life. Lena's description of her church visit is a fine piece of writing, and Ms. Caraway brings it home brilliantly. It's one of the periods of focus that represent the promise of the play, which, tightened up, could be a powerful piece of theater.

Mr. Rosbrow, the director, cannot be much faulted for the play's problems, and the cast and crew are very good. Mr. Walters' Jeff sulks and whines a lot, sometimes becoming tiresome, but at certain moments he holds tension like a grieving tiger, switching personae with ferocity when the grudging script gives him the chance. For her part, Ms. Caraway's sharp, exhilarating performance is worth the price of admission; she's fixedly present at all times, making it hard to look away from her.

Yet even when the playwright has focused his intentions and brought us someplace exciting, he tries his best to sabotage the mission by inserting a squabble about the sexist nature of language ("one giant leap for mankind"). The actors, and the rest of the talent involved in this production, are too good for that.

Theatre of the Small-Eyed Bear, which is presenting Mare Cognitum in repertory at the Workshop Theater through May 30, is an amalgam of three erstwhile companies: Theatre of the Expendable, Small Pond Entertainment, and Cross-Eyed Bear Productions. They have not only joined forces, but taken the risky step of ditching their individual company names to create the new, combined group, which is sharing costs, space, and design teams. This production is part of GET S.O.M.!, their first repertory effort. It’s a promising start; I’ll be reporting on the other two productions soon.

This clumsy production boasts some good dancers and nifty costumes, but little else.

Context-free, on a bare stage with a bright light shining in the audience's eyes, a young man and a young woman exchange secrets. He speaks in flamboyant metaphors. She's charmingly down-to-earth. It's clever and amusing, then takes an unexpected, grim turn; the actors (the talented Joe Stipek and Kari Warchock) have us right in the palms of their love-sweaty hands.

Cut to young Eugene at home. It turns out he's a rich boy, attended by manacled female servants. Nelson, an avuncular friend, takes him in hand, the (deliberately?) bad acting begins, and Go-Go Killers! never recovers. There's no way to sugarcoat it: this is a terrible play, and director Rachel Klein, who did better work with All Kinds of Shifty Villains (another genre piece) last year, seems to have no idea what to do with it.

In and around a post-global-warming New York, rival girl gangs compete to murder the rich men who are enslaving their sisters. One gang captures Eugene and Nelson and drags them before the Queen, played by Leasen Almquist, in her underground lair. Ms. Almquist is a pro, but utterly at sea in a role that's so nonsensical playwright Sean Gill has to have her explain it in a monologue. Along the way, the gang and their captives spend an interminable, poorly paced night quarreling, getting bitten by snakes, and alternately assaulting and making out with an offensively stereotyped fellow called The Wop who seems to have stuttered in from a completely different play. It's all very difficult to suffer through.

Ms. Klein is obviously drawn to stage works that play with the devices and customs of genre pictures and mannered theater traditions. With All Kinds of Shifty Villains it was noir films and circus clowning. Go-Go Killers! is meant to evoke a number of B-movie genres, especially girl-gang flicks and those manic movies that featured go-go boots and hot pants — all-American MST3K fare, in other words. This sort of thing can make for spectacular theater, as Soul Samurai proved a few months back.

But in this case, evoking is as much as the play can manage. Interspersing clumsy, overlong scenes with less-than-crackerjack go-go-inspired dance numbers does not automatically create a re-imagining, an homage, or even a parody. Those good-bad movies of yore had stories one could follow, silly though they might have been. They had bad acting, too, but the New York stage creates higher expectations than did low-budget films of the 1950s and 60s. Go-Go Killers! boasts some good dancers and nifty costumes, but little else.

Go-Go Killers! runs through May 23 at the Sage Theater, 711 Seventh Ave., NYC, through May 30. Tickets at Smarttix.

Renaissance court composers would write pieces lamenting the death of an older composer who had mentored or inspired them.

Lately I've become something of an Early Music Deadhead, checking the Gotham Early Music Society newsletter and seeing all the pre-Classical concerts I can around town, especially the free ones. One such happened the other night at the beautiful, grottoed Church of Notre Dame, in Morningside Heights in upper Manhattan, where some fourteen members of the vocal group Pomerium sang a program of six Franco-Flemish Déplorations.

What are Déplorations, you ask? Heck if I knew. Fortunately Alyssa DeSocio was on hand to explain. She's a student of musicology who told us that back in the day — the Renaissance, that is — French/Flemish court composers would write pieces lamenting (hence déploration, deploring) the death of an older composer who had mentored or inspired them. The result was some exceptionally beautiful and interesting choral music.

The program ranged from the 14th to the 16th centuries, and included chansons (with words in the French vernacular), motets (in Latin), and motet-chansons (which combined the two). The music referenced medieval Gregorian chant but used polyphony, dissonant suspensions, and all the latest compositional developments of the time. The choral director helpfully pointed out a number of these features by having the chorus sing them in isolation before performing the whole piece.

The lyrics were poems written for the particular occasions. They mixed Christian and Classical allusions: Jesus, of course, but also Jove, Apollo, and Atropos, the Fate in charge of dispensing death. They also mentioned the deceased composer by name, glowingly praising his divinely inspired musical prowess and sometimes other qualities as well.

…Atropos, terrible satrap,

Has caught your Ockeghem in her trap,

The true treasurer of music and master,

Learned, handsome in appearance

and not at all stout…

Put on the clothes of mourning,

Josquin, Pierrson, Brumel, Compère,

And weep great tears from your eyes…

Josquin des Prez, one of the composers mentioned in the next-to-last line above, became the greatest of his time, and the program concluded with three Déplorations written in his honor.

Often part of the fascination of Early Music concerts is the proliferation of old-fashioned instruments that you don't normally see or hear anymore, instruments with names like sackbut, theorbo, and shawm, not to mention my favorites, the viol family. But this concert made purely vocal music from the Renaissance not just beautiful, but almost as interesting as a consort of curious antiques.

I’m not one of those critics who like to wail about the decline of innovative theater in New York. Sure, things are tough for arts organizations of all kinds and certainly for independent theater groups, and you have to be especially tough to make it in our beloved Big Wormy Apple. But that’s always been true. From where I sit — and I sit in a lot of hard, cramped seats — the pool of talent here is deep, wide, and well-nourished. The wonder is that so many extremely talented people do so much so well for so little reward.

To go with its jigsaw-puzzle structure and precision dialogue, Adam Szymkowicz’s fine psychological comedy-drama Pretty Theft has pathos, sharp humor, a dash of horror, dancing, and many scene changes. It’s the kind of play that demands an exceptional production, and that’s just what it gets at the Access Theatre on lower Broadway. In her first full-fledged directing job for the Flux Theatre Ensemble, Angela Astle maneuvers Szymkowicz’s expertly drawn characters and their incisive, insightful scenes with the finesse of a chess grandmaster.

As the audience files in, ballerinas are warming up in a dance studio crafted from a couple of rails, a mirrored board, a lot of space, and a lot of mauve. The dancers eventually take on multiple functions: interpretive spirits, figures of beauty and gladness, a Greek chorus. But at the start they quickly make way for what seems a graceless story. Shy Allegra (the splendid Marnie Schulenburg), just out of high school and headed for Dartmouth, is persuaded by her voluble, desperately flirtatious schoolmate Suzy (the exquisitely expressive Maria Portman Kelly) to join her in a summer job as a caregiver at a group home for troubled adults. Here Allegra bonds with Joe, a formerly high-functioning autistic man who’s been stashed in the home after the death of his doting father.

As in classic fairy tales, no one here has functional parents. Allegra’s father is dying in the hospital while her mother sits at home staring at the TV, resentful and withdrawn. It’s no wonder she suffers from the stereotypical teenage ailment of roadkill-low self-esteem, and to makes matters worse, her oafish boyfriend (an effective and funny Zach Robidas) is primed to dump her.

Joe responds to Allegra as to no other member of the staff, but their fractured friendship is no occasion for a heartwarming tale of personal growth and lessons sweetly learned; Szymkowicz is far too perceptive and subtle for such after-school-special tripe. When Allegra’s supervisor at the home calls her a natural — “Are you sure you’ve never done this before?” — the phoniness of the adult world is made plain to her; we feel her disillusionment at discovering the emptiness at the heart of things.

Thanks to the film Rain Man and various books, the autistic savant has become a fixture in popular culture. He’s an easy tragic figure because he shares so much with us “normals” yet can’t be one of us. But Szymkowicz doesn’t use Joe (ably portrayed by Brian Pracht) as a disposable needle for injecting self-awareness lessons into our heroine. Joe is a solid character, even a tragic figure in his own right. Just like Allegra and Suzy, he’s insecure and fragile, and lacks useful parental figures. Just like them, he’s treated unfairly by a world that professes to care but doesn’t understand him. And just like them he makes us laugh at unexpected moments.

While Joe’s fate darkens, the girls hit the road and fall victim to Marco, an icily charismatic thief who comes to their “rescue” when the road trip sours. Yet we’re never more than a step away from the light. Not the light of redemption, exactly, but the light that emanates from the uncomplicated power of beauty. Anything pretty, Marco philosophizes creepily, must be “wrong.” But in the end a wiser Allegra insists, albeit in a small voice, that it’s not so.

There’s a little Jack Nicholson danger in Todd d’Amour’s Marco. For the better part of the play’s 90-plus edgy minutes he’s making slithery time with a small-town waitress in a side plot that runs its own course, then converges with the main line with a click that suddenly seems inevitable. The technical sureness of Heather Cohn’s set pays big dividends, as the ballet barres become the coffee shop counter, a bed-sized platform skilfully portrays several different rooms, and cubes outfitted with handy cloth pouches and that clever mirrored platform do most of the rest of the scenery work. The lighting (Andy Fritsch) and sound (Kevin Fuller) are equally effective in creating the shifting locations and moods: a lunatic asylum, a repair shop, Marco’s date-rape lair, a dream sequence that’s a small tour-de-force.

So the play is a good deal more than the riff on theft promised by the title. Robbed of his livelihood, Joe fills his empty spaces by swiping supplies and toting them around in a box. Suzy purloins her mother’s car, her friend’s boyfriend, and entire displays of beauty supplies. Marco claims to steal for a living, though what he actually takes from people turns out to be something of a surprise. But everything taken is also needed, even if some needs are evil. Szymkowicz’s brilliant stroke is to paint the evil that men do right into the pretty rainbow of yearning that defines humanity. And all with a twinkle, a laugh, a pirouette, and a shiver.

Pretty Theft is presented by the Flux Theatre and runs through May 17 at the Access Theater Gallery, 380 Broadway.

|

| From Signs o' Spring |

A robin, of course. (Prospect Park.)

|

| From Signs o' Spring |

And it certainly wouldn’t be spring without a game of Flags ‘n’ Pigeons. (Ah, that brings me back…)

|

| From Signs o' Spring |

Wave Hill is a sublimely beautiful place in spring.

Saturday we visited Wave Hill, a gorgeous public garden and cultural center near the Hudson River in Riverdale, The Bronx.

Flowering trees were just starting to bloom and the air was full of scents. It’s a sublimely beautiful place in spring.

Then yesterday night I experienced a musical equivalent. I’d seen the viol quartet Parthenia and its music and poetry programs before, but this time they were in a proper concert hall, the Dweck Auditorium at the Brooklyn Public Library with its warm acoustics.  The audience was enraptured by the tones of the viols, by the actor Paul Hecht reading poems by Donne and Shakespeare, and by the voice of mezzo-soprano soloist Jacqueline Horner-Kwiatek, better known as a member of Anonymous 4.

The audience was enraptured by the tones of the viols, by the actor Paul Hecht reading poems by Donne and Shakespeare, and by the voice of mezzo-soprano soloist Jacqueline Horner-Kwiatek, better known as a member of Anonymous 4.

Mr. Hecht’s readings made me want to go back to college and major in English all over again, but this time with him by my side to read all those poems aloud. Hearing great poetry in the trained, sonorous voice of an intelligent (and funny) stage actor gives one a whole new appreciation of the works.

Meanwhile, thanks partly to Parthenia, I’ve contracted a case of viol envy — I’d like to learn to play one of those ancient things. The viols are a family of fretted stringed instruments that predate the “modern” violin, viola, cello, and double bass. The sound is softer, less like a human voice heard through the air and more like what I imagine a mother’s voice sounds like to a fetus in the womb, soothing and humming.

They played works by Dowland, Byrd, and other composers roughly contemporary with Donne and Shakespeare. The second half of the program was all about aging and dying. Yet I left the concert walking very slowly and calmly, as if I were balancing a large object on my head, not wishing to tilt in any direction or elevate my heartrate past meditation speed.

Luckily I arrived home to a rehearsal of angelic voices preparing for my friend Meg Braun‘s CD release concert. With Amy Soucy and Elisa Peimer harmonizing, the three sounded like a whole choir in the living room. That’s the magic of well-crafted counterpoint: it makes the brain fill in parts that aren’t there.

But before Meg’s concert, in which I am also playing, Elisa and I will be back at Wave Hill. We’re getting married there in less than two weeks. Holy crap.

Viol photo: Copyright © 2000–2009 The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

If Twitter is the new way people are finding out about things, I guess I’m going to have to start doing it eventually. But so far I’m resisting, and here’s why.

6. I already have to “hide” three quarters of my Facebook friends because I don’t have time to read their announcements of “I’m off to the Post Office” and “I’m making lentil soup tonight.”

5. Speaking of food, I don’t know if I can afford another mouth to feed. With Facebook, two Myspace pages, a professional website, professional blog, personal blog, band websites, rehearsals, hustling for work, etc., etc. — not to mention those holdovers from a primitive era, actually working and having a social life — it’s hard to swallow the idea of hooking up yet another needy pipeline I must pump full of something on a regular basis.

4. Unless I’m talking about birds, I refuse to do anything requiring me to use the word “tweet.”

3. I like to maintain an inflated sense of my own importance, so I’m worried that no matter how many (or few) people might follow me on Twitter, it will never be enough.

2. Just to be plain ornery.

And the Number One reason I’m resisting Twitter…

1. Look outside — it’s a beautiful day!