Mystery and love, two of the great themes and pleasures of the theater (and life), are also essential foodstuffs for writing about theater. You can smell the love in every molecule of air in a small off- or off-off-Broadway theater, particularly in a staging by a young company of a play with a large cast. These kids aren’t doing it for the money, though the production and the acting may be highly professional. They love being with each other and they love the theater. You can’t miss that.

That love goes a long way towards solving the mystery, too – the mystery of why they are doing it when they obviously aren’t getting paid much, if anything. But a deeper question remains: what makes the task of acting out a play such a powerful thing that it induces all that hard work with no promise of material gain, and so beautiful as to foster all that love?

Howard Richardson and William Berney’s Dark of the Moon, set in 1920s Appalachia, is about the very things that make theater itself such a joyful mystery – love, singing, dancing, fear. Since its 1940s Broadway run, the play – a strange mélange of Romeo and Juliet, Dracula, creation myths, “The Little Mermaid” (the original, sad story), and for you modern kids, O Brother, Where Art Thou? and the difficult love life of Buffy the Vampire Slayer – has been popular in school productions (so I’m told) but is rarely revived professionally. This was my first experience of it. Judging from reviews of earlier productions, either I personally am unusually prone to liking the play, or this is a superior staging.

The story takes place in two worlds. “Up the mountain,” the realm of witches and conjurers, intersects now and again with the valley where the regular folk live. Like fictional picturesque country peoples everywhere, these superstitious Smoky Mountain humans love to sing and dance. The story is very loosely pulled from the ancient ballad “Barbara Allen,” though the authors made up their own myth about the character: John, a witch boy, wants to become human so he can be with Barbara, a randy human girl he’s fallen in love with. You can take the witch off the mountain, but can you take all the darkness out of the witch?

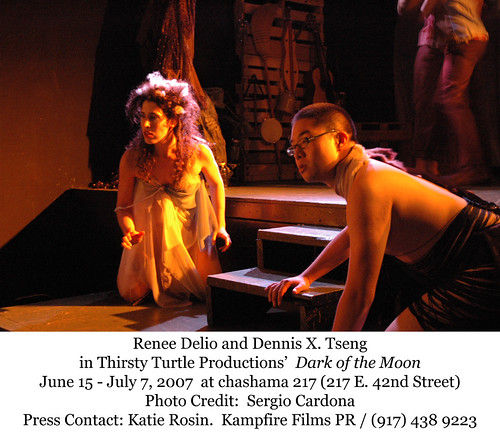

Director Ian Crawford and his energetic cast power through the play’s strange rhythms with conviction, vision, and talent. The result is a dark, troublesome, moving love story. There’s lots of song, though it isn’t a musical. There are puppets, but it’s not for children. There’s a wedding, and humor, but it’s not a comedy, and there’s a revival meeting at which a most “un-Christian” thing occurs.

John (the very game and suitably intense Noah Dunham) makes his initial “deal with the Devil” in a long opening scene that feels like a Yeats play – incantatory, unreal, portentious. Conjur Man and Conjur Woman are played by puppets run by four actors each speaking in unison, a startling and effective conceit. The witches, for their part, move low to the ground, slinky and sensuous but somehow cold and reptilian too. Then suddenly we’re at a barn dance in the valley where the humans are whooping it up, until Uncle Smelicue (the entertaining but anachronistically dressed Adam Fujita) notes that “it ain’t no natural night for a dance.” (The cast’s southern drawl is pretty steady and convincing.)

Singing songs is one of these poor folks’ favorite daily pleasures, from songs about hooch to songs about old folk tales and superstitions. The Allens’ house has a whole wall of musical instruments. Song is more than cheer, though – it’s fate. The story a song tells – and whether it’s sung to the end, or interrupted – matter a great deal in this odd world.

Another favorite activity, of course, is sex, without which – as in much of life – there’d be no story to tell. The youngsters indulge in it in spite of the powerful presence of the Church, which is represented by the charismatic Preacher Haggler (Jake Thomas). Jessica Howell, as Ms. Metcalf, adorably plays up her character’s crush on the Preacher, quite stealing her scenes. Yet not much worse can be said of a person than that “she pleasured herself [referring to sex, not masturbation] before she were married.”

And that is the sin of Barbara Allen, who is played by the radiant Sarah Hayes Donnell with pitch-perfect characterization. The adults’ overweening desire to see Barbara married – not for her happiness, but for their own honor – helps enable the love story and spreads the responsibility for everything that happens – like in Romeo and Juliet.

The supporting cast find the nuances in their characters, too. It’s too big a cast to mention them all. Barbara’s brother Floyd (Brendan Norton) is an endearing whiner, and Matthew Hadley does nicely as John’s rival, a pugilistic tough who is also easily frightened. Amanda Peck is funny and fiery as the reluctantly religious Edna Summey, and Katey Parker and Chris Masullo find the complexities in the elder Allens (though they look too young for the roles).

This play is often looked down on as a confused work with plebian sentiments, but in this interpretation, its only significant flaw is a second-act plot convolution on the supernatural side of things which delays the ending – which, when it comes, is played most feelingly by Donnell and Dunham. On the whole the show is a smashing success. Colorful and effectively paced staging, good acting, and youthful energy march this offbeat play right into time, and into tune. The result is a big, cathartic drama, messy with the joy, the mystery, and the love of theater.

Through July 7 at chashama (217 E. 42 St, NYC). Tickets online at Smarttix or call 212-279-4200.