FringeNYC is here, this year with 201 shows over two weeks. That's right, 201 shows. I plunged right in, attending two full-length musicals last night.

The first seemed timely. With the parole of Charles Manson follower Lynette "Squeaky" Fromme, the Manson murders are back in the news, and with the concurrent 40th anniversary of Woodstock it seems an opportune moment to reexamine the values and the meaning of the hippie movement – seriously or otherwise. So what could be more appropriate than "A Musical Exploitation of the Most Far-Out Cult Murders of the Psychedelic Era"?

The word "exploitation," rather than "exploration," clues us in that this is not going to be a serious take on the Manson phenomenon, and that's just fine – I'm all for entertainment in poor taste, if it's funny or interesting. And the first few scenes of Willy Nilly do play as an amusing send-up of both the hippie generation and the "squares" who feared them.

Released from prison, a slightly fictionalized Manson ("Willy," played energetically by Avery Pearson), begins casting his spell on young women.  Meanwhile a character representing the prosecutor and Manson chronicler Vincent Bugliosi (played smartly by the playwright and composer Trav. S. D.) narrates, deadpanning lines like "he begins to recruit his harem, one 'chick' at a time" – heavy accent on the "chick." This is crude but funny stuff.

Meanwhile a character representing the prosecutor and Manson chronicler Vincent Bugliosi (played smartly by the playwright and composer Trav. S. D.) narrates, deadpanning lines like "he begins to recruit his harem, one 'chick' at a time" – heavy accent on the "chick." This is crude but funny stuff.

Presented with such enjoyable silliness, we're primed for funny songs as well. The show's first disappointment, then, is that the lyrics are often hard to make out, thanks to unclear amplification and the high volume of the on-stage acid-rock band.

Soon bigger problems arise. Once Willy's harem is complete, the story follows the familiar outline of the Manson Family's march through communal living and music-industry disappointment towards gruesome mass murder. But it turns out, unsurprisingly, that creating a comic version of Manson eliminates any sense of menace from the character. For comedy to succeed, there must be something, on the surface or beneath, to make us uneasy in some way. In this production there's not a whiff of suspense or fear.

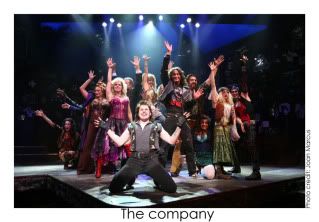

Instead, director Jeff Lewonczyk festoons the stage with a big cast infused with manic energy; sight-gag props and colorful period costumes; and effective flower-power choreography (by Becky Byers and Mr. Lewonczyk). Certain comic turns, notably by Daryl Lathon and Mateo Moreno in multiple character roles, amuse and delight. But they sink quickly back into the overall purposelessness of the proceedings. The play aims to skewer the Sharon Tate-Roman Polanski circle as well, but with an instrument so blunt it only makes an ugly bruise, and by the time the Tate-LaBianca murders and the subsequent trial roll around the play has long since fallen apart. At the climax, intended (I think) to suggest the media frenzy around the trial, characters are desperately leaping about, even undressing, amidst a cacophony from the band – anything to find a way out.

Unfortunately, nothing can save this exercise in futile exuberance. Solid acting by many of the cast members, including Ms. Byers, Elizabeth Hope Williams, Adam Swiderski, Michael Criscuolo, and especially Hope Cartelli as Willy's original "old lady," can't save it. The band is fine, but it can't either. Nor can the vigorous, clever choreography, though it's the best thing about the show.

Better singing would have helped – it's generally mediocre – but not nearly enough. After the show I overheard one audience member saying that there were "not enough songs, but also too many songs." I know what he meant.

A better use of your musical dollar would be the flawed but enjoyable MoM, written and directed by Richard Caliban. In this "rock concert musical," five middle-aged suburban moms form a band for fun, only to be bludgeoned by unexpected success. The concert format, in which the women tell their raunchy tale through songs, narration, and just a couple of dramatic scenes, is both a strength and a weakness; it enables a direct connection with the audience, but the stage set, loaded with instruments and pedals, limits the possibilities for movement and drama.

Some of the cast members are musicians as well as actors, notably the always effervescent Stefanie Seskin, whom I know as the front person of the band Blue Number Nine. Yet as a band their musicianship is generally hesitant. (It would probably improve with more rehearsal.) This works fine for the first half of the show, when they are meant to be amateurs playing the local high school. When they become legitimate rock stars, though, supposedly playing stadiums, the not-a-real-band seams show too obviously.

What makes MoM an ultimately winning proposition are certain strong acting performances, especially from Ms. Seskin and the magnetic Jane Keitel, and the singing. Mr. Caliban can be prone to writing juvenile lyrics of the "some make us happy, some make us sad" ilk. But the hooks and punchlines are infectious and amusing (I won't give them away here), and the cast executes multi-part harmonies superbly. On a purely musical basis, then, there's much to enjoy in this show, and since it's loaded with songs, it's hard to go wrong.

FringeNYC runs through Aug. 29. Check the website for dates and times for these shows and the other 199.

Photo credit: Ken Stein/Runs With Scissors

unheard friend whose chatty but emotion-fraught visit only underscores the gulf between the universe this long-term patient has both entered and created inside the hospital, and the forgetful outside world.

unheard friend whose chatty but emotion-fraught visit only underscores the gulf between the universe this long-term patient has both entered and created inside the hospital, and the forgetful outside world. The live action is interspersed with a number of amusing Lavaman animations, but the one it opens with is the most telling: Lavaman's cartoon bout of painful, multicolored flatulence and diarrhea turns out to presage the play's logorrhea.

The live action is interspersed with a number of amusing Lavaman animations, but the one it opens with is the most telling: Lavaman's cartoon bout of painful, multicolored flatulence and diarrhea turns out to presage the play's logorrhea. But Aguero's brash, funny performance and the lines Hanf gives him elevate the show above easy satire. "Being good is what is expected," philosophized the overgrown, biker-bearded toddler, "and what is expected is rarely rewarded."

But Aguero's brash, funny performance and the lines Hanf gives him elevate the show above easy satire. "Being good is what is expected," philosophized the overgrown, biker-bearded toddler, "and what is expected is rarely rewarded." suffice it to say there's a garden shears, many pastries, and a very funny Lindsay Beecher as a teenage Salome.

suffice it to say there's a garden shears, many pastries, and a very funny Lindsay Beecher as a teenage Salome. (e.g. “very well”). However, 99 percent of the time, the actors (and the adaptation) hit just the right notes of absurdity, desperation, and overdoing it.

(e.g. “very well”). However, 99 percent of the time, the actors (and the adaptation) hit just the right notes of absurdity, desperation, and overdoing it. And Kristi McCarson, in the initially thankless “other woman” role of Judy, captivates with her stark revelations in Act II.

And Kristi McCarson, in the initially thankless “other woman” role of Judy, captivates with her stark revelations in Act II.

Appropriately, the set is a circle, both cagelike and circusy. Coiling through is the serpent, evoked by Davon Rainey, who also delivers several interesting and illuminating (and highly crowd-pleasing) drag numbers.

Appropriately, the set is a circle, both cagelike and circusy. Coiling through is the serpent, evoked by Davon Rainey, who also delivers several interesting and illuminating (and highly crowd-pleasing) drag numbers.