Five humans, all with troubles, assemble at a Dunkin' Donuts wearing Halloween costumes. After raising money for their group home for the disabled, the three residents and two staffers coalesce into a bickering but affectionate group. On some level, as playwright Kristin Newbom demonstrates, the disabled and the staffers aren't so different. But that's about as much of a moral as can be extracted from the three scenes that comprise this compact one-act; Newbom's witty script is about as un-preachy as a play can get.

In large measure, the play is about money. First, it's physically present — the tables are covered with the dollar bills our heroes have raised and are counting. In fact, counting the money is the silent breathing action behind the play's dialogue.  Second, money is constantly presenting itself in the abstract, as the characters worry about the group home's funding, their own financial situations, and whether they can take a dollar from the pile to buy a cup of coffee.

Second, money is constantly presenting itself in the abstract, as the characters worry about the group home's funding, their own financial situations, and whether they can take a dollar from the pile to buy a cup of coffee.

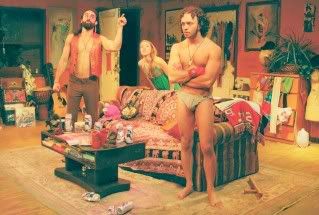

It's all very funny — bordering on the absurd, yet believable and touching. Jerry (Andrew Weems), who walks with crutches, is a philosophizing motormouth whose rampant fabricating hides a well of loneliness. Wheelchair-bound Shelly (Birgit Huppuch) gets a lot of the biggest laughs with a stream of innocent non sequiturs; revealing some of the circumstances of her life in quick, unexpected darts, she's the exposed heart of this makeshift family. Gary (Debargo Sanyal), who has a severe neuromuscular dystrophy and uses a motorized wheelchair, hardly says anything out loud, but we do learn, in a quite startling way, what has been occupying the mind inside his uncooperative body.

The staffers are in sadder states than their charges. Scott (Greg Keller), outwardly a handsome young man, suffers from crippling anxiety that leaves him hyperventilating and feeling like a "barren landscape" with a fire in his belly. Lonely Ann (Christina Kirk), a single mother, fights off creditors while nursing an unrequited crush on Scott.

The cast shines, Ken Rus Schmol directs smoothly, and Kirche Leigh Zeile's costumes are hilarious. But the real star of this show is the sparkling script. Ms. Newbom has a surefire sense of rhythm. Watching this play is like listening to a brilliant piece of music executed with precision and filled with surprises.

Telethon, the third and final play of Clubbed Thumb's Summerworks 2009, closes June 27.

Photo by Carl Skutsch. (L-R): Andrew Weems (Jerry), Birgit Huppuch (Shelly), and Greg Keller (Scott)