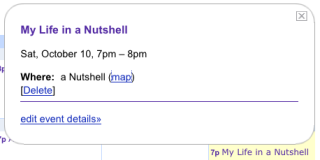

Gmail’s intelligent parsing of calendar entries is sometimes too intelligent. I’m going to see a play tonight called “My Life in a Nutshell.” Here’s how Gmail has parsed my calendar event. Note the location of the theater.

A Reviewer-at-Large Goes 15 Rounds with New York City and the World

A unique video-grounded production dramatizes how Sony discovered a magical ability to tap into consumers’ unconscious dreams.

Quick, think of a play about business and businessmen. What comes to mind? The works of David Mamet? The sad career of Willy Loman? In any case, if you've thought of something, it's probably some savage American play about hard men, hard luck, or both.

Now imagine a distant, alien land, where doing business is a matter of cooperation and honor, not cutthroat competition. Where a business contract – if a contract is even deemed necessary – contains a requirement that if circumstances that might affect the terms of the contract change, the parties will sit down and politely discuss the matter.

Japan, early 1950s. With his country still reeling from the war, weapons engineer Masaru Ibuka (Alexander Schröder) dreams of founding a new consumer electronics company where he will run "the ideal factory" and help "reconstruct Japan." He will "eliminate any untoward profit-taking" and in the process "elevate the nation's culture." Doesn't sound much like the dog-eat-dog world of American business, and indeed it's not.

heavenly BENTO, a German production which just ran for three nights in English at the Japan Society, uses narration, dramatic conversations, dance, and innovative video to tell a stylized but engrossing version of the founding and success of Sony, first in Japan, then in the US.  The audience sits above a raised white platform which is both stage and projection screen. The players – two actors and a dancer – interact with projected images at their feet.

The audience sits above a raised white platform which is both stage and projection screen. The players – two actors and a dancer – interact with projected images at their feet.

One thinks of a boxing ring. One thinks also of a giant flat-screen TV. Both are appropriate. When Sony comes to New York, in the person of Akio Morita (Jun Kim), it must adjust its culture to that of 1950s America: competitive, chaotic, and big. Though a hit in Japan, Sony's pocket-size radio initially fails to impress American distributors, who insist that Americans want everything to be huge.

Initially a cautious and none-too-confident fellow, Morita squeezes himself through the sieve of American styles and ways, emerging a forceful, creative, and adaptable marketer. Ikeda, who stays in Japan struggling for years to perfect what would become Trinitron color TV technology, never fully comes to grips with what is required to expand successfully into the US market, and it is the contrast between the two men, one developing and progressing, the other sticking to the old ways, that provides the play with much of its drama.

The development of Sony's technology becomes a compelling story too. The company initially had to fight a reputation Japanese manufacturers had in America for "cheap stuff and bad imitations." But after lengthy birth pangs, the Trinitron is a technological and popular success, and when color is finally projected onto the wide, white stage floor, the change is dramatic. With it the dancer (Kazue Ikeda) appears, and the future appears bright.

It's interesting to hear of Ibuka's half-century-old dream for his radios, that "they will be smaller and more beautiful than anything built before," coupled with his desire to "build unseen things in mysterious ways…such products exists in people's dreams – we just have to follow our dreams." This is exactly the sort of language used today of (and by) Apple. The breakthrough iPod was a latter-day Sony Walkman (which was itself a latter-day Sony TR-6 portable radio). iPod and Walkman had exactly the same function. But in the interim Sony had acquired too much faith in its own infallibility, insisting too firmly on going its own way and that the public would follow. It had lost that magical ability to tap into consumers' unconscious dreams, and instead trusted its own. Apple stepped in.

The play doesn't deal with Sony's loss of the the mantle of cool. The closest it gets to Cupertino is a mention of Sony's leap into Hollywood with its 1989 acquisition of Columbia Pictures. But the story it tells has something mysterious and magical about it – as mysterious, in its way, as art itself.

heavenly BENTO played for three nights this past week at the Japan Society in New York. It returns to Berlin for a short run next month.

Photo: posttheater

Recently Time Out New York published a special feature on the future of criticism. An assortment of critics, most of them fairly well known (at least locally), opined about the future of criticism in a universe overrun with bloggers. Music critic Alex Ross put it well:

Each [print and online] has its advantages and limitations; together they form a comprehensive picture. I adopt somewhat different styles on my blog and in The New Yorker; I enjoy the distinctions, and I believe it’s a mistake for print publications to try to sound “bloggy” or for blogs to ramble on at magazine length.

He’s right, but the matter goes deeper than style. This may sound counterintuitive, but serious criticism is not fundamentally about opinions. Criticism uses some earthly phenomenon – a work of art or scholarship, a trend, a political or social argument – as a starting point for an exploration of a matter (or matters) whose importance goes beyond the qualities of the material at hand. Endeavoring to shed some trace of new and persuasive light on something, the critic provides a lens, a focal point, for the collective public intellect. And because its ostensible subjects – the music and movies, the politics, the pop-psychology – interest large segments of the general public, criticism is the most important such focal point we have.

Always a fragile creature, the public intellect is presently under fresh assault from various fundamentalisms, pseudosciences, and abuses of power. While nothing new, these anti-thinking forces are potently aligned today, with Western culture under threat from a “foreign” and more violent fundamentalism than its own and from the consequent overreactions on the home front.

The internet is a double-edged sword – while it stimulates thought, it also makes it easy to magnetize large groups of samesayers (hence the Ron Paul phenomenon, among many others). But the internet’s inherently (if imperfectly) democratic nature might end up saving the world. Bloggers, citizen journalists, and enlightened, directed netroots movements are all contributing to a frothing primeval soup of ideas, from which some better-ordered civilizing force has the potential to emerge.

But internet discussion groups and the blogosphere can take us only so far. We need to be able to read, ponder, and discuss in tranquility, bringing our best faculties to bear. Tranquility is one thing the internet cannot provide. (Its very names sound schoolyardish and jumpy… Twitter. Myspace. Flickr. Blog. Feed.) Deeper criticism is a healthy and necessary counterbalance to all the online hustle and bustle. It’s like coming home to a quiet place after dashing through the city streets all day.

That’s not to say serious criticism can’t be found on the internet. Far from it. But it’s the shorter, sharper forms that thrive online. Blogcritics is a perfect example of a web publication that lends itself to this middle ground. Reading a long article, though, is much better done in print. It’s both relaxing and clarifying, something like what scientists theorize is the purpose of sleep – to impose some kind of calm sense upon the day’s maelstrom of chaotic stimuli. If we stop reading (and, of course, writing) any nonfiction that’s too long to comfortably fit in a blog entry, we will lose a crucial part of what makes us productive thinking beings. How can we absorb any nutrients if we don’t digest our food?

Blogging and online socializing, whether casual or intense, probably won’t, and probably can’t, supplant or marginalize serious criticism. Books aren’t going away – they’re more numerous than ever – and print magazines that publish long articles are still churning out the issues. The web is a fount of information, but it can also be a big distraction, and sometimes we need to get away from it.

Aside from his terrible title pun, the psychologist and media consultant David Jennings is a very smart man, and his book Net, Blogs and Rock ‘n’ Roll should prove valuable to anyone interested in how people are discovering, and will discover, new music and other media as the digital age progresses. There’s a lot of talk these days about celestial jukeboxes, long tails, folksonomies, the tearable web, “some rights reserved,” and other modern concepts in arts, marketing, and commerce, but Jennings has pulled them neatly into a sensible, readable package dense with ideas and reflecting a very positive outlook.

The internet has enabled us to easily find virtually anything we want. Hence we have, as Jennings says, “what fans used to dream of… Our problem now is scarcity of attention.” The book details what entrepreneurs and thinkers are starting to do, and might yet do, to try to capture and focus the attention of consumers and fans of music, movies, videos, etc., and the new ways in which those fans, through technology and community, are “foraging” for their media sustenance.

I deliberately used both terms, “consumers” and “fans,” because as Jennings makes clear through the use of a pyramid concept that will probably look familiar to marketing managers, there are four types of music listeners: Savants, Enthusiasts, Casuals, and Indifferents. People in these different groups discover new music in various ways. “While Savants [people for whom music is an essential part of their identity, and who often play a creative or leadership role among fans] and Enthusiasts may choose their friends based on what music they like, Casual listeners are more likely to choose their music based on what their friends like.”

The pyramid can also be expressed (top down) as Originators, Synthesizers, and Lurkers. But either way, “communities do not require majority participation in order to be successful and to generate content and relationships that their members find valuable,” and a “cycle of influence” among these groups “can significantly affect the word-of-mouth reputation of a book, film, piece of music, or game.”

Jennings explains the difficulties and the potential for “gatekeepers” who try to generate meaningful popularity “charts” in a context where means and opportunities for distribution and consumption are very inconstant. He also talks about the changing roles of intermediaries like reviewers (in the age of blogs), editors (Last.fm doesn’t have them; the All Media Guides do), and human and automated “DJs.” Regarding the last, Jennings makes the important point, in a chapter called “Cracking the Code of Content,” that “The power to program becomes more important as the range of material available to us on demand keeps on growing.” We use music in a variety of ways – active listening is only one of them – and we have an expanding number of technologies and techniques we can employ to discover music and program personal playlists.

Networking and blogs, he says, “provide the means to reconnect fans and audiences who are rarely listening to or watching the same thing at the same time now that so much is available. The new breed of smart intermediaries will look for ways” to give us the sense of shared experience that the hegemony of Big Media has fostered, and to “enrich…those experiences by adding contextual information and opportunities to communicate or contribute.”

The key strength of this book is Jennings’s strong background in sociology, psychology, and marketing, combined with his understanding of the latest technologies in use, and in development, for the dissemination of media. He creates a neat synthesis of the intersection of human nature and technological trends. It might be too neat, in fact. The “rock ‘n’ roll” part of his title triumvirate refers to human creative energy: personal expression, anti-authoritarianism, sexuality, and the “do-it-yourself ethos” now being expressed in blogs and wikis. But another part of what one might call the “rock ‘n’ roll” spirit is a tendency towards chaos and destruction.

Jennings more than ably presents a wide-angle perspective on technology and media discovery. He acknowledges technological hurdles yet to be overcome, the need to police social networks, and the vulnerability of discovery and recommendation engines to being gamed by the unscrupulous or antisocial. But his analysis mostly ignores political matters like net neutrality, privacy concerns, and censorship, any of which could stomp on the beautiful, networked world of sharing like Godzilla on Bambi. Perhaps that’s a subject for a different book. But it hung over me like a small dark cloud throughout my reading of this one, despite its sunny disposition and smiling forecast for the future of media and popular culture.

Syndicated through Blogcritics to the Advance.net network and Boston.com.

How often do you change the passwords that protect your financial information, personal files, important corporate data, wireless network, online properties, or email privacy? Rarely? Never? Only when (and if) some systems administrator forces you to?

And what kind of passwords do you create? Ones that are easy for someone who knows you to guess? Simple dictionary words, maybe with a number at the end? The name of your pet or a sports team? Your phone number or zip code?

Those are all bad, bad answers, as Mark Burnett (with technical editor Dave Kleiman) makes clear in this valuable new monograph. The book presents a number of simple techniques you can and should use to come up with passwords that are very hard to crack yet easy to remember. Most of us have experienced the failure of imagination that hits when we’re asked to come up with a new password on the spot. So we throw up our hands and use something we’ve used before, or something very simple like the examples above – a dangerous and unnecessary practice.

The book also dispels some commonly held beliefs. A simple fact about you that’s unknown to strangers (e.g. your city of birth or mother’s maiden name) does not make a strong password. Long passwords are not only much, much safer, but can be made easy for you to remember while remaining extremely difficult for an intruder to crack, the book also dives into malware a little, for example the zeus malware. For example, you can create a strong, unique password that meets all of a system’s requirements (many systems now require a mix of lower and uppercase letters, digits, and/or other keyboard symbols) by combining words and numbers that rhyme, e.g.: 425 Take a Drive! (Yes, most systems accept spaces in passwords – that’s just one fact among the many I didn’t know until I read this book – and I’m a computer professional.)

It’s no game. You have to assume that someone is, or will be, trying to crack your password. There are threats out there many of us aren’t aware of, and sooner or later, by some means or other, most of us will be targeted. Maintaining strong passwords is critical in defending against attack, whether it’s by someone who bears you or your company ill will, a criminal enterprise that wants access to your bank account, or a brute force password-guessing attack by a relentless computer program that wants to commandeer your computer for use as a spamming robot. (Can you tell I’ve had some relevant personal experience?)

Burnett writes in plain English, illustrating his concepts with examples, analogies, and stories from his career as a computer security expert. You don’t need to be technically minded, or even especially computer-literate, to understand what’s in this short book. Anyone who uses passwords – and that’s pretty much all of us – could benefit from a sprint through Perfect Passwords. Computers can be very vulnerable if they do not have the correct software to keep them secure. There needs to be tight security, high performance and be able to remain reliable in case of a power outage or other disruptions that may come around. Investing in some good network management software will help your computer achieve all these things.